Survivorship By Us

At risk of sounding like a broken record, I must remind you that we live in the Information Age. It has transformed every aspect of life across the world, but especially in the West where much of our industry and manufacturing have given way to knowledge work. The most visible economic sector of our brave new world is media. It’s what we spend much of our time looking at and talking about, after all. It has quite an outsized influence when you consider how few people are actually employed full time in content creation. Your limited ability to perceive all the world all at once means some manner of media lies between you and whatever you want to know about over yonder, mediating (ha ha) your relationship with the unseen.

There are criteria for what data make it into these media pipelines, entirely invisible to you. Media may not exactly be giving you an accurate picture of reality. In fact, I believe it has magnified the worst of human biases to create a modern crisis where the most inquisitive among us are enthusiastically embracing highly inaccurate world models. Accepting this claim does not require you to believe in some conspiracy. The crisis is entirely accidental.

That’s it. That’s the thesis statement. You can stop reading now.

I: The Sieve

I don’t know when it happened, but at some point the word “media” transformed to refer metonymically to the news media by default. “The media” became a synonym of “the press”. That’s unfortunate because the silent conversion of “media” to “press” is going to really confuse you unless you consciously put it out of your mind in favor of what I really mean: media as the plural of medium. Mediums of what? Information. News are media, but so are movies, books, blogs, podcasts, music, video games, emails, text messages, and interpersonal face to face conversations. Media are how one human sends some information to another in any form besides literally bringing them physically to the source of the information and letting them perceive and experience it themself.

By this definition, media are always lossy, like a jpeg. No ultra detailed description of a beautiful mountain coupled with a high res photograph can even begin to approach the experience of being there in the flesh. That’s because subtle stimuli like temperature, humidity, air pressure, odors, the wind, etc. all contribute a significant amount to the emotive properties of outdoor experiences. It is possible that we will eventually develop media that more accurately articulate these aspects of physical presence too(GIVE ME SMELLOVISION), but right now we’re missing quite a broad range of stimuli. I oftentimes find myself associating books in my mind with how the weather felt while I was reading them rather than any vibes they were intentionally trying to elicit.

Survivorship Bias Refresher

If this diagram activates the proper neurons, skip to the next section.

The famous parable illustrating survivorship bias goes thusly:

In the thick of WWII, the US military was always intensely gathering data and pursuing interventions that would give them an edge in combat. One such study was conducted on bombers returning from bombing raids over Europe. They hoped that by charting where planes were most often hit by surface fire they could determine where to deploy more armor on the underside.(Q: Why didn’t they just put armor everywhere? A: It would add too much weight.) Their data collection efforts yielded the chart above. Take another long look at it. Where should the military deploy their armor?

The naïve response would be to say on the wings, where the damage was observed most frequently. If you think it over for a moment it becomes obvious that the reason there is absolutely no bullet holes in rest of the aircraft is because those planes didn’t make it home. Damage to the cabin or the fuel tank or the bomb bay would lead to a fiery crash and no data collection afterward. The answer—somewhat counterintuitively—is to armor the hull where you didn’t observe damage.

Survivorship isn’t always relevant

Survivorship bias is simply the phenomenon of observations being confounded by some sort of selection pressure. One might observe that ancient cultures tended to build their structures out of sturdy stone. But they certainly built many wooden structures too, they just collapsed or burnt and didn’t survive for centuries to be observed by us.

If we stay wise to the effect, we can still learn something from the data. But not every scenario is created equal. The plane example could be made useful simply by inverting the chart. But what about the structures? The lack of surviving wooden structures does not necessarily imply their previous existence. The Kiribati people had very little timber and mostly built their structures from stone as well as palms, leaves, and even coral. This is why the plane example is a poor one, because it makes survivorship bias seem like not that big of a deal—just invert the data! Unfortunately, reversed stupidity is not intelligence and it’s often not even obvious what to invert.

What happened in St. Louis this weekend?

Odds are, unless you live there, you have no idea what happened there this weekend. And if you can tell me something that happened there this weekend, odds are it was pretty extremely bad. Let’s apply our survivorship insights to the presence or absence of this datum. What does it tell us? That no news is good news and we should take every uneventful weekend as more evidence that St. Louis is a pleasant place to live?

Did you know it has the highest violent crime rate in the United States? The chances are greater than even that what happened this weekend was somebody was murdered! The data that ranks cities in the U.S. by violent crime rates is pretty easy to find, easy to interpret, and at least somewhat relevant to your life. What could explain the fact that this isn’t how any normal person forms her opinions about how safe a city is?

When the internet started penetrating the home of the average consumer, the image peddled to us was an infinite library of human knowledge, only keystrokes away. Gone were the shortcomings of physicality, overcome by endless digital bandwidth faster than thought. For the correct brain, this is exactly what the internet can be. A library one billion times greater than the greatest library ever assembled, and one billion times more convenient.

Tragically, the vast majority of us do not have the correct brain. We lurch through life from treat to treat, always seeking the next little splash of dopamine. The information landscape evolved to suit our needs (it always does) and our library of all human knowledge turned principally into an endless rack of tabloids with some dusty archives in the back. In the present state of things, the media diet of the average American is sort of like a food diet comprised entirely of Frito-Lay products.

This is not meant to be a judgement of woe upon the wicked people of the land of the free. This end state was inevitable given the witches’ brew of human psychology and capitalism. There’s not much to be done about it on a macro level beyond committing unspeakable acts of political violence, but that doesn’t mean the situation isn’t worth examining and understanding for our own edification. You and I could buck the trend.

The Darwin Derby

The same selection pressures that explain the behavior and appearance of organisms also explain the behavior and appearance of media. There is a finite quantity of human attention that media compete over in the same way that organisms compete over resources, and media that fail to capture attention usually fail to reproduce in the same way an organism that starves may fail to pass on its genes. When we look at organisms we can usually intuitively understand where many of their behaviors and attributes come from. The bee stings so that all bees may have a reputation for stinging, warding off predation.

So what are the adaptations we have observed in media, especially as the landscape for transmitting information has radically shifted in the past decades? Well, I could probably go on about news getting more sensational, optimizing for rage-bait, misleading headlines to get you to click, playing a game of telephone by relaying stories broken by other publications so very little “news” is actual original reporting. But we’re not just talking about the news. We’re talking about all media. More importantly, all of my claims about the press could be 100% factually incorrect and you would still be hopelessly in the clutches of survivorship bias. As long as we accept that media are only made because they are anticipated to be consumed—which sounds tautological, honestly—then we have a clear, intense selection pressure that is going to taint all of your data. Several, in fact!

All media you will ever consume will have run a gauntlet of selection pressures:

- Somebody thought it was worthwhile to produce

- That individual had the resources to produce it

- There was some sort of economic justification to expend those resources, or the stakeholder felt it was so worthwhile for non-economic reasons (e.g. political campaigning for the purposes of gaining power, this blog for the purposes of ???) that they would eat a resource loss

- They marketed or distributed it widely enough that it reached you

- It is in your language and in a format accessible to you (e.g. not on a wax cylinder)

- You found it interesting enough to click on/purchase/look at.

If you were a scientist trying to create a model for some social phenomenon, any one of these confounders would be enough for you throw out the data, because it’s hopelessly biased and unrepresentative of any base reality. And these selection pressures are extant in all research and science too! It goes by special names amongst the uncommonly self-critical scientific community: Publication bias, Replication crisis. But it’s all the same beast. A distortion field through which no human-generated content can penetrate without having been profoundly unnaturally selected.

II: The Algorithm

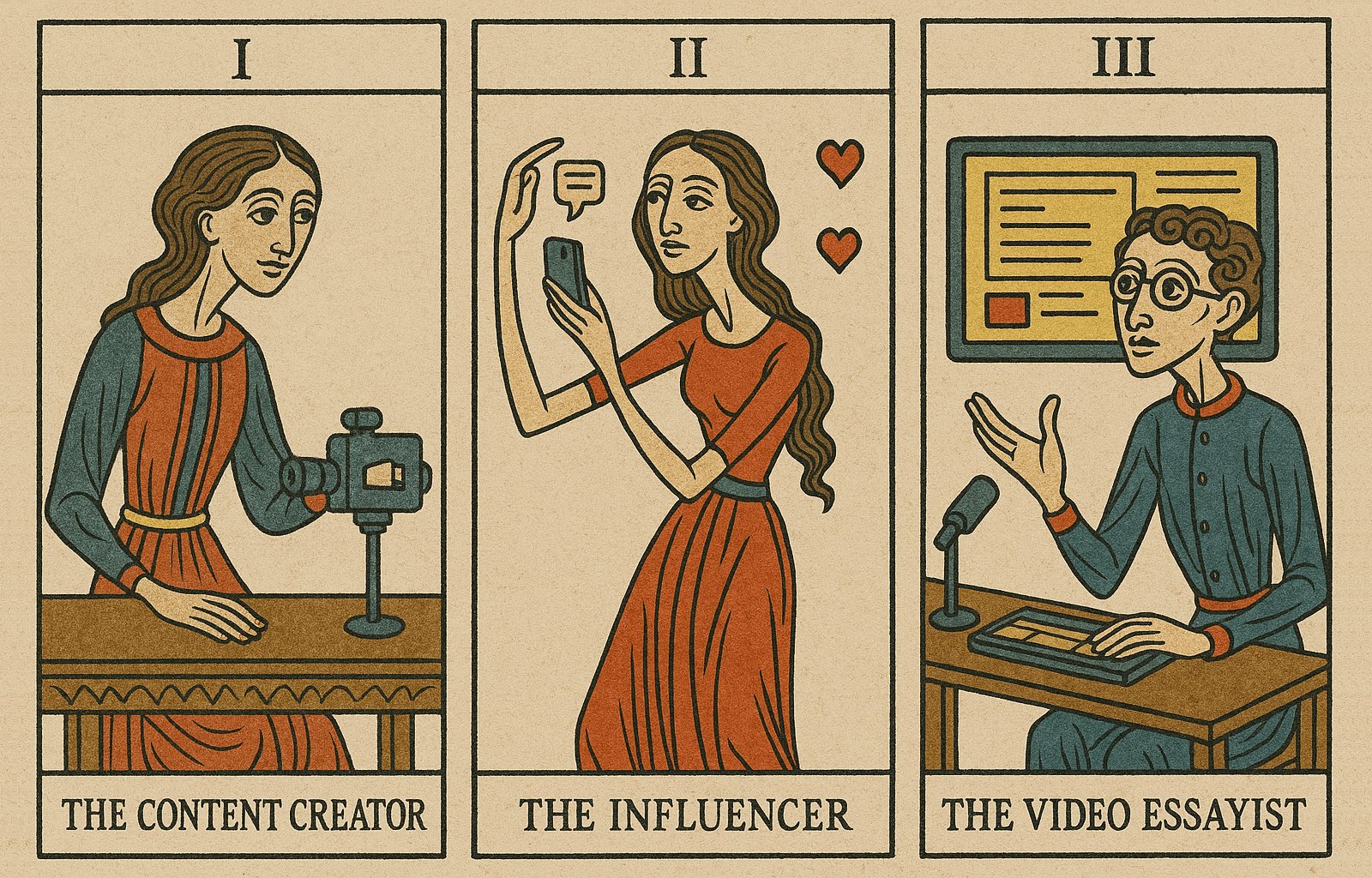

If we envision the sum total of all information about reality as particles traveling through a Sieve(or perhaps a pachinko machine) of selection pressures that filter out 99.9999…% of it then one may wonder what happens to the little pittance of information that manages to exit out the other side, the media that manage to get produced, distributed, and discovered by you. In the modern era of global media up until the late 20th century, you were were mostly beholden to a few tiny groups of huge industry gatekeepers: the big 5 movie studios, the big 5 book publishers, The C.P.R.R. Big Four, Pulitzer and Hearst. The world wide web dislodged this hierarchy in a big way, causing a publishing golden age that minted an entire major arcana of everyman media figures: the Content Creator, the Influencer, the Video Essayist, the Commentator, the Reactor, the Blogger.

We’ve also received a new batch of gatekeepers, the platforms upon which these media creatures depend upon for their continued existence. The feed-based apps have a very strong incentive to connect you with content you want to see (so they can show you more ads), putting their finger on the scale very forcefully on your behalf. We call it The Algorithm, an adaptive software product that uses your past behaviors (and the past behaviors of everyone else) to predict your future choices and make them for you. It is true that The Algorithm has been meddled with by humans from time to time to further political goals, test methods of social control, or cozy up to despots. But they always eventually revert to the mean, the forever liquid power-broker of ad spend connecting with viewer interests.

The nature of The Algorithm is to intensify the distortion of The Sieve by several orders of magnitude. But many err in placing the blame for the state of our information landscape entirely on social media companies, as if the rest of human history was far more enlightened and unified. This is extremely myopic because it fails to recognize that The Sieve is a base building block of human existence, one that defined our superstitions and conflicts throughout history. Our natural sensory bandwidth and the literal curvature of the Earth have conspired to mislead us ever since we first stacked one rock on top of another and called it media.

Why do I insist on tearing down your trust in all human knowledge? After all, rationality is systematized winning, and humans have been on a major winning streak as of late what with all the agricultural revolutions and antibiotics and stuff. I contend that down and dirty empiricism was the secret sauce here, not necessarily well fleshed out world models informed by academic consensus, since the consensus at the time of the aforementioned wins could be straight up wrong. For every Borlaug there is a Malthus, for every Alexander Fleming a Franz Mesmer. All of our efforts in knowledge-sharing can mislead just as easily as they inform. Some of the most stunning leaps forward in art, research, and philosophy came from someone you might describe as ignorant, or at least heterodox.

Embarking on any self-directed learning in the tradition of the empiricists can bring you to this conclusion quite quickly and cast a sickly pall over your experience with, say, public education. Our curricula and benchmarks for schoolchildren seem to be chosen almost at random, especially in the humanities. The moment I stepped foot in a university-level history class I realized I had to toss out most of my world-model that had been built on a public school curriculum that was optimizing for something far stranger and more complex than the mere prosaic value of accuracy.

Unfortunately, for most of our fellow travelers the phrase “self-directed learning” means obediently gobbling up whatever The Algorithm deigns to serve you and getting sucked into a spiral of tendentious and totalizing ideology. If we could assign a floor and a ceiling value to how “accurate” any one Sieve can be, the vast library that is the internet has raised that ceiling dramatically and yet The Algorithm has driven the floor into the depths of hell, and clearly lowered the accuracy score of the average Joseph’s world model. Alas, there is no return policy on the internet.

III: The Survivor

One very popular medium on the web is human language, borne by the vessels of The Post, The Podcast, The Blog, The Shortform Clickbait Video. Individuals talking and writing. A lot of the time, these people will deliver The Take, a claim about the world that they wish for you to consider. They will fairly often deliver The Take with a high degree of confidence and certainty, because empirically they have found it to be true. If I’m such a big fan of empiricism, I should be a big fan of these Takes, no? If I’m advocating for a foregrounding of individualistic world modeling above the paradigm of societal knowledge building, then these brave souls cutting against the grain should be my heroes, no?

No. I’m quite happy that The Take has served them so well, but allowing it to breach containment in the form of advice on the internet turns it from effective personal empiricism into the much more sinister anecdatum(I’m calling it this annoying made up word instead of “anecdote” because I believe that word—anecdote—has accumulated several embedded meanings that distract from my thesis on singular data points being shared as media). It does not take very many anecdata to overwhelm your audience’s commitment to sample sizes and error bars and p-values. It takes years of scientific training and study of common failure modes to understand why all these esoteric scientific concepts matter (and how easy they can be to falsify!). You may notice those in academia and research have a little bit of a credentialist superiority complex—a priesthood, if you will—that I suspect stems from one too many close encounters with the stupendous credulity of the hoi polloi.

Sometimes one single anecdatum from a respected source is enough to set the course for someone’s frame of thought and information diet for decades to come. My frame-setting respected source Scott Alexander—who has accomplished more than probably any other individual in shaping my world model—demonstrates exactly how easy it is to overwhelm someone’s rationality with anecdata by convincing the reader that cardiologists are more evil than the general population.

What me, Scott, and Gwern are all trying to convince you of is that consuming news and novelty-driven educational content is just as likely to mislead you as it is to inform you, so as a mind-cultivating activity it’s a wash at best and actively harmful at worst. Quoth the Gwern:

I’m going to go a little further than Gwern and claim that The Sieve should make you suspicious of all information you receive (even trends and averages!) that you did not specifically go looking for. Furthermore, this zone of suspicion should extend outside of the usual suspects—news sites and social media feeds—to your interpersonal relationships in meatspace. People don’t suddenly become more rational when all the relevant data is not longer at their fingertips and we’re all hazily recollecting something we read somewhere by someone that claimed… uh… something.

Each voice that reaches you is that of a Survivor, someone who has accrued enough influence, resources, proximity, and luck to have the chance to deliver The Take. And when the Survivor speaks, they are merely the mouthpiece for that bias that was named after them. There are a lot of decisions I have made in my life that have worked out for me, and others that I felt have harmed me. I fear if these anecdata were to breach containment in the form of Takes they would merely serve to prove my Survivorship rather than my wisdom.

Epilogue: The Scientist

I wrote this essay to caution anyone against fancying themself “informed” because they’re well-read, or stay up to date with the news. I didn’t advocate too forcefully for an alternative epistemology, which I know may be frustrating, because I don’t feel entirely confident one exists. We may just be doomed, required to embrace most of our personal world-model with very low certainty to have true epistemic hygiene. That being said, I do have a flimsy theory for why personal empiricism might actually be a step in the right direction.

Human brains are pattern matchers and puzzle-solvers. We aggregate a breathtaking amount of sensory data into an array of specialist semantic models that enable us to achieve a high level of dynamism and success in the grueling state of nature (and the similarly grueling human society). The upshot of all of this is each human brain is extremely custom, and they don’t interface with each other quite right. We misread each other’s body language, we misinterpret the meaning behind each other’s words. Descartes was right: you can only really trust yourself, and all else is deception, maybe?

This is a pretty crazy claim that runs counter to most scientific common sense about how to build knowledge: create a community, gate it with credentials, and make everyone pick each other apart constantly to only allow the pure truth to bubble to the top. I think this process is great! But what we commoners do with media isn’t really science, and what scientists tend to do with published science isn’t really science either, it’s public relations. So this essay’s thesis was about how other people’s PR isn’t really that useful to you. But my sub-thesis is that you can spend effort synthesizing your own personal custom anecdata for your own personal custom world model. It’s far more useful for you than somebody else’s anecdata.

If you plumb the subterranean depths of your subconscious you will find your pattern-matching mind is relentlessly tagging and categorizing inputs in a way that is mostly invisible to you. This means what you experience, know, believe to be true, carries an iceberg’s worth of latent embeddings specifically tailored to your experience and circumstances. Sometimes it goes by the name of cognitive bias, and some of it is truly useless (e.g. the gambler’s fallacy) but some it can be quite beneficially adaptive. I’ll leave it as an exercise for the reader to ascertain exactly which of their biases are maladaptive and which are merely useful data compression techniques.

Position yourself as The Scientist, where the subject under consideration is your life, and the data is all of your experience. Ponder deeply on these things. Don’t be afraid to synthesize outside information like the dreaded Media and The Take, but always with a cocked eyebrow of suspicion and a remembrance of how your epistemic immune system has been overcome in the past. I believe this is the beginning (but not the middle and end) of the path to securing all of the good things in life like peace of mind, spiritual fulfillment, career success, a likable and cheery disposition. It will insulate you against radicalism and ideology, remove you from the exhausting treadmill of current events, and unmask your once-forgotten childlike curiosity.

Or maybe not. It was just a thought I had.