Mo Meta Mo Betta

In a past life I watched a lot of video essays on YouTube (I’ve since given up that vice, more on that later). These videos had the incredible ability to engage, enrage, and move me, when the topic was prosaic as speedrunning a game that I’ve never played. These sort of documentary-style deep dives into a community or individual doing battle against an arbitrary goal—creating and solving higher dimensional Rubik’s cubes, making a legendary run at the world yo-yo championship, or beating Super Mario 64 in the minimum number of A-presses—are absolute crack to me. The funniest thing is I really don’t care that much about the underlying narrative substrata: cubing, yo-yoing, Mario 64. But once you surround that with a scaffolding of community, competition, drama, etc. then it suddenly becomes ultra compelling to me. What gives? How can we take advantage of this phenomenon to make our own work more compelling?

This is the first entry in a new series I’m doing on storytelling in the 21st century. Humanity has been making up and relaying stories since we figured out language, but the main ways in which we receive and relay ideas have been upended by advances in technology. In Medieval Europe a restless mind who wished to tell stories should probably have optimized for learning an instrument so they might become a bard and join the oral tradition. In the early modern era, learning to write and finding someone to publish you would have been the best course of action. In the late modern era, one might need to take care to attend to their looks and presentability as video came along to kill the radio star. And now, more eyeballs and earholes than ever are being fought over by a thousand million clapping dancing screaming content creators: bloggers, youtubers, tweeters, comedians, musicians, developers, authors, celebrities, influencers, streamers, podcasters, journalists, advertisers, each begging to get their grubby hands on a little tiny sliver of your finite pool of attention for the day. A lot of them are driven by the marriage of money and passion. I mean, who isn’t? Everyone wants to make a living doing what they love.

But I’m going to err on the side of passion with my recommendations, I make no warranty or guarantee for the economic viability of implementing what I’m about to say. I think there are deep and powerful ways that the frontier of storytelling has expanded in the last decade that are being underexploited by true artists and perhaps overexploited by canny attention farmers with a dearth of artistic vision. So where were we? Ah yes… since video killed the radio star, who killed the video star?

Claim: Humans like Humans

We’re coming around to year 3 of the AI slop revolution and the humans have still not all been swept away in a tidal wave of machine productivity as its boosters keep giddily predicting. Some of my colleagues and friends think this is because AI is worthless scamware, but I don’t find that very defensible when a well designed AI Art Turing Test is already defeating our discernment. Some others are in my ear claiming that they just need a couple more years and a couple more trillion dollars and everything will click into place, but this exponential capabilities growth curve is starting to look a little bit like an S…

What if the reason I haven’t been replaced by Mr. Claude isn’t that he needs a little bit longer in the oven. What if the reason is because my coworkers don’t want to get lunch with Mr. Claude, they want to get lunch with me. What if the crazy people that get to decide who gets hired want humans they can interact and socialize and collaborate with.

To generalize: it seems like many consumers don’t just merely want the productive outputs of other humans, they also value the authorship tied to those outputs. If I could make a completely computer generated version of Love Island where all the contestants were algorithmically optimized to be on the cutting edge frontier of hotness and pettiness, I still think the viewers would drift away toward a less perfected human cast that would keep on existing after the show ended. If I could generate the most gripping thriller novel of the year, I still think the readers would prefer books by the flawed authors they already know who go on political rampages on twitter.

I don’t think this is a rule that holds fast in all situations. A lot of big budget mass media is totally alienated and anonymized from the creators—who directed the latest Marvel movie? who produced Taylor’s newest album?—and that could probably go AI without much fanfare (except for getting clowned on by the usual AI is evil crowd once it is outed). But in general, I’m going to make a weak prediction that generative AI isn’t going to make much of a bigger splash in the art and media world than any other tool like Photoshop or CGI. Those were still pretty big disruptive splashes, but they created more jobs and opportunities, not less.

So no, I don’t think AI killed the video star. I think video games killed the video star.

4D Art

Woah, OK, I know not everybody plays video games. But you may be surprised just how many do. The industry generated an estimated $187 Billion in revenue last year. That’s more than film, music, or print publishing. Not quite as much as TV, which rakes in the cash via huge and steady streaming subscription revenue. But it’s easily a giant of media, and one of only two minted in the past half-century. The other? Social media, the clear number 1 by revenue.

What do vidya games and endless algorithmically curated feeds of content have in common? Well, both are more addictive than any previous media format. But what underlies and explains that pathology? It can’t be the audiovisual component, or the packaging, or the convenience. The mighty smartphone has made all forms of (digitizable) media equally extremely convenient to consume. No, I think it’s mostly the interactivity and the feedback to that interactivity. Whether it’s a joystick or a comment section, a character creator or a profile picture, you participate in the narrative of these media. This has the effect of drawing you back in to discover new developments, try new techniques, to hone your skills and earn plaudits, to touch the pond and see it ripple. This is just not possible in any other medium, and it never will be (Bandersnatches notwithstanding).

So if interactivity is the defining characteristic of cutting edge 21st century narratives, how’s that scene doing? The good news is that the scene is enormous. The bad news it that the scene is enormous. You are both guaranteed that something perfectly catered to your preferences exists out there and also doomed to never find it. I recently went to a meetup where I got to witness (in the flesh!) Scott Alexander and Sam Kriss—blogging’s oddest couple—argue (very civilly) about whether a world with a singular great piece of art was preferable to a world with 1,000,000 bad pieces of art and 2 great pieces of art. Sam preferred the former and Scott the latter. I won’t wade into the minutiae of the general aesthetic decline that Sam seems to believe is occurring, but I think it’s pretty clear we do in some way live in the world where the bad art (if the concept of “bad art” is offensive to you, feel free to substitute in “media that you personally don’t find appealing”) greatly outnumbers the good. It was a great conversation but I really must restrain myself from regurgitating the blow-by-blow details.

For me, good art optimizes for profundity, elegance, novelty, with a dash of psychological manipulation, while bad (yet competent) art goes right for the psychological manipulation and mostly ignores the rest. I am well aware that what I tend to prioritize—especially as far as social media and video games are concerned—is far removed from the mainstream. It has made me grow more interested in the psychology of gamers instead of the games themselves.

The tasteful dash of psychological manipulation I was referring to is often the aforementioned human element. If humans truly do like humans, then a good way to make your piece of art more compelling is to get real humans—not human-shaped characters, real people with legal names and government documents!—involved in your story. Non-fiction amplifies the drama (true crime) and amplifies the comedy (Nathan For You). But non-fiction also has major constraints (events need to have actually happened, and they will always obey physical laws) that can interfere with creativity. I think the golden middle is to author a creative and imaginative work that recommends itself to be a foundation for new, human, never-before-possible stories to be told. This is why I think (some) games represent a completely new frontier in art: their interactivity makes them sort of in superposition between fiction and non-fiction because the act of playing really happened.

It is these methods of play, some of them quite counter-intuitive—cubing, yo-yoing, Mario 64—that inspire people to devote extreme effort to mastering them, accidentally creating dramatic real-life narratives that yet others are inspired to chronicle and relay to me.

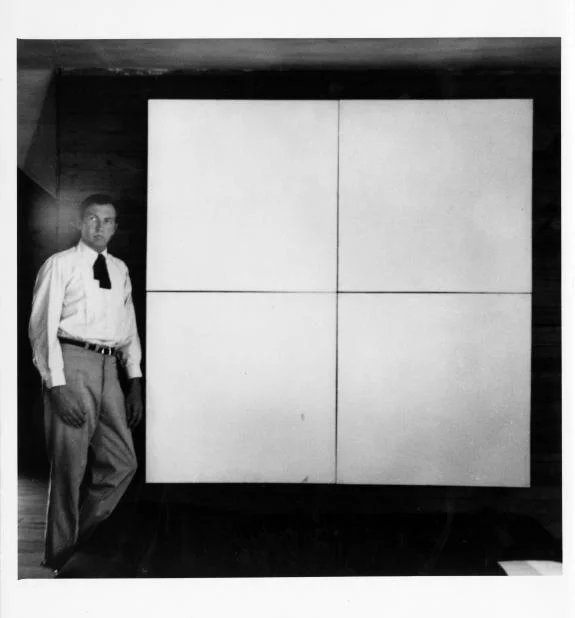

During a gold rush, sell shovels. Maybe the most profound piece of art is the blank canvas.

Minecraft

Some games like Tetris seem to inspire human excellence because of their iconic simplicity. Others like CounterStrike function like sports, pitting people against each other for extreme stakes. For my money, the best game functioning as a narrative substrate—let’s call this type of thing a “gamecanvas”—is Minecraft. It’s the GOAT, it’s not even close, but it also might not be for the reasons you think.

Minecraft takes place in a 3D world of blocks extending out infinitely, populated with various beautiful natural biomes, tainted by supernatural phenomena, dotted with humanoid settlements and other randomly generated structures. Every world is different and every playthrough is different due to the procedural nature of the world, but also owing to the sheer amount of content that a game like this can offer when it has been under active intensive development for over a decade: dozens of biomes, dozens of structures, dozens of animals, dozens of monsters, thousands of unique items and blocks. It’s a game with such extreme diversity that it can look and play shockingly different from hour to hour.

All these things are important to making it the greatest gamecanvas ever made, but they aren’t the whole story. There are lots of sandbox games that provide equivalent or even greater levels of freedom, there are MMOs that have an order of magnitude more content, and there are games like Tetris and Mario 64 with tighter systems. Minecraft excels because it marries all of these together, acts unopinionated about how exactly you should engage with it, and then invites you to extend it. Minecraft’s modability and somewhat realistic and nondescript core experience makes it the nighest a game can come to being a white canvas. An extremely accessible white canvas that has inspired thousands of young people to create completely thematically disjoint gaming and narrative experiences that still exist within the fundamental constraints of Minecraft proper. Let’s explore a few.

Man vs Hunters

Dream is a divisive figure for many good reasons, but he’s not one of the most popular Minecraft creators of all time for nothing. He came up with a fairly simple idea: he tries to beat the game (yes, despite being a sandbox, Minecraft can technically be beaten, in just a couple minutes under ideal circumstances!) while somebody else tries to kill him (in Minecraft). If he dies once (in Minecraft), he loses. The important thing to note is that he’s absurdly good at the game while his hunters are sort of hamming up their incompetence like the bumbling stooges of a supervillain. This dynamic leads to some exhilarating moments, countless tiny near misses, tragedies (he loses sometimes!), and the general limbic activation of a really good action movie, all the while being more or less (you do eventually get the feeling after he narrowly avoids death for the billionth time that there may be a degree of scripting involved) non-fiction. Some of these videos have gotten over 100 MILLION views, more than the population of all but a few countries. They grow increasingly absurd along with the stakes, going from Minecraft Speedrunner vs Hunter to Minecraft Speedrunner vs 5 Hunters Finale Rematch over the course of a couple years. If you have even a morsel of interest in this, I invite you to watch one of them, even if you have no idea how Minecraft works. Just behold what a unique viewing experience has been constructed on top of this gamecanvas.

The thing I find myself appreciating about Minecraft while they’re playing it is how unobtrusive yet deep it is as a setting. The manhunt idea is compelling all on its own, but the variety of mechanics, weird interactions, diverse locales, and rare occurrences (and maybe a touch of kayfabe) whizzing by during the average hunt promises new surprises every video. Call me cringe, but I find this level of novelty more engaging than any gameshow or reality show I’ve ever seen.

Man vs Nature

A popular form of Minecraft video is the humble challenge. The game by itself isn’t that hard to beat once you’ve mastered it, so creative players have pushed the boundaries of what you can even do in the game. Some beat it really fast, which a popular approach in many games. But they also beat it with only one block in the entire world, or farm a million melons in 100 days, or beat the game starting from what seems to be a completely unbeatable starting scenario, trapped in a featureless unbreakable expanse.

This is not unique to Minecraft at all, many games inspire people to beat them under strange constraints. But only a small handful (Mario 64 once again comes to mind, also Runescape) have such dynamic systems that allow for this breadth and depth of approaches to the game.

Man vs Narrative

Minecraft doesn’t have a story beyond the player’s own actions. So some people create their own stories in Minecraft using the power of the gamecanvas they’ve been handed. There’s the infamous Parkour Civilization which plays sort of like a shonen anime with vine booms after every sentence.

And then there’s ish.

Ish is well known for doing massive events with hundreds or thousands of players like he’s the Mr Beast of Minecraft (ignoring that Mr Beast is also known for doing massive events with thousands of players in Minecraft). He encourages the participants to roleplay via a strong sense of setting and theming, yet manages to avoid railroading them. He is, in essence, building a canvas on top of a canvas. So when he has 1000 players simulate civilization in Minecraft, leading to a feature film’s worth of political upheaval, Shakespearean betrayal, and wacky character arcs, there’s still room for a second feature film told from the perspective of a single participant caught up in forces beyond his control, with a bizarrely poignant ending that explores the tolls of war and survivorship guilt. In the block game for children!!

Narratives are powerful creations that can move and change us. Metanarratives—stories built on top of an underlying narrative, in conversation with the author or the audience, can magnify that effect. So my first piece of advice to the aspiring creative is to figure out if there’s any way you can make space for a metanarrative to be organically constructed.

Many of the more business-minded media enterprises have caught on that having an engaged community is highly lucrative, and you can often see them cynically attempting to nurture one that serves their interests. I think this strategy doesn’t work very well from an artistic standpoint, because communities usually don’t align with the author’s desires. Which is what makes them interesting! If you can simply make room for a community to grow—and people on the web have gotten very good at forming passionate enthusiast communities around banal topics—without coming off as too cloying or desperate, you’re setting yourself up for unique human drama. That might not feel like a reward if you find conflict a distraction from your own work, but sometimes the community and what they manage to create and experience is simply more interesting than your work. You still deserve authorial pride for creating the conditions that enabled the rise of the metanarrative.